By: Yigal Schleifer / Washington

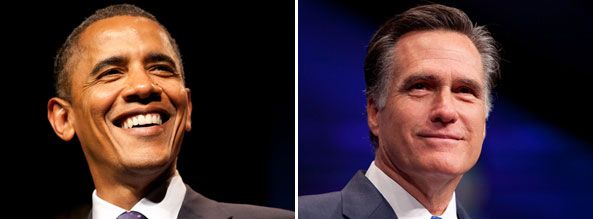

American President Barack Obama and his challenger, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, have been spending this election season working hard to portray themselves as each representing a starkly different choice for American voters.

But as the last debate in Florida between the two candidates made clear, when it comes to foreign policy issues, Obama and Romney are not really that different.

During the debate, Romney frequently agreed with positions that the Obama administration has taken on many key foreign policy issues, or offered only mild criticism on others, leaving very little distance between the two.

“On foreign policy, the similarities are more striking than the differences between Romney and President Obama,” said Michael O’Hanlon, director of research for the Foreign Policy program at the Brookings Institution, a Washington, DC-based think tank.

When it comes to the question of Turkish-American relations, the debate – which featured hardly any discussion of Turkey itself – ultimately answered very little, leaving observers to continue their guessing game as to what the election would mean for the ties between the two countries, particularly if Romney were to win.

In the case that Obama is reelected, the picture is fairly clear. Although Obama presided a rocky period in Turkey-US relations, particularly during 2010 after the Mavi Marmara incident and the Turkish “no” vote in the United Nations Security Council on tightening sanctions on Iran, the period since then has seen a dramatic improvement in the ties between Ankara and Washington.

“I think President Obama’s views are well known. He has worked hard to cultivate a strong personal relationship Prime Minister Erdogan. At all levels, Turkey-US relations are better probably today then they have ever been in history,” said Ross Wilson, a former US ambassador to Turkey and currently director of the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center at the Atlantic Council in Washington.

Indeed, while only a few

years ago Washington was filled with questions about whether Turkey was “drifting east” and if Ankara could still be considered a reliable ally, today that kind of talk has been mostly pushed to the background. Instead, as the upheaval in the Middle East has helped reignite the previously struggling Turkey-US strategic relationship, Washington has come to view Ankara as an increasingly crucial ally.

“If you listen to what the administration says, Turkey is a critical partner regarding what’s happening in the Arab world, in Afghanistan, in Syria. We’ve built a real relationship here and it’s not just based on the president’s personal relationship with Prime Minister Erdogan,” said Steven Cook, an expert on Turkish affairs at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“If Obama is reelected, we can expect more of the same,” added Cook.

The picture for Turkish-American relations is less clear with Romney, who has said very little about Turkey publicly and has given few clues about what his Turkey policy might be. The presence among Romney’s team of foreign policy advisors of several figures linked with the neoconservative movement and George W. Bush’s brand of aggressive foreign policy could be of some concern to Ankara. The fact that one of those advisors is former ambassador to Turkey Eric Edelman, who has been a strong critic of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government in the past, could be especially worrying for Turkish policymakers.

But the Atlantic Council’s Wilson said that Romney’s performance at last week’s foreign policy debate could be an indication that the influence of the neoconservatives on his team is limited.

“I was struck by the tone and tenor of Governor Romney’s remarks in the foreign policy debate, where he was clearly working to tack back to the center in American politics,” said Wilson.

With Ankara and Washington working closely together in so many areas, CFR’s Cook said a Romney presidency would simply not have much room to change the US’s Turkey policy. “Perhaps the tone will change and Romney will not be calling Erdogan on the telephone as much as President Obama, but I don’t expect the overall quality of the relationship to change,” Cook said.

Ultimately, it’s in an area where the two candidates are in agreement – a refusal to allow the US to get involved militarily in Syria – that could cause the most trouble for Turkish-American relations after the election.

As Soner Cagaptay, an analyst of Turkish affairs with the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, wrote in the Washington Post in early October, considering Washington and Ankara’s divergent policies on Syria, “a storm between them appears almost unavoidable.”

With the crisis and violence in Syria likely to only worsen in the coming weeks and months, the situation there is going to present a major challenge to Turkey-US relations – regardless of who gets elected to be the next American President.